FILMING IN TUNISIA IV

Sun rise in Mos Eisley

Few have thrilled to that experience.

Few have wanted to.

But here we were again; Sir Alec, Mark and me, beginning to feel like an oddball concert party, visiting some very strange venues and performing our speciality acts for the unfathoming audience.

Another day. Another place.

A long time ago.

Of course we weren’t alone. We travelled with a large retinue and a lot of baggage. We travelled in cars and buses, spewing diesel fumes into the clear desert air.

We brought food and water. We carried umbrellas to shield us from the sun and reflectors to bounce the sun around us, if it was being inconvenient and doing its own thing, as Nature intended.

Today, no floundering in some ghastly, unthinking desert, no panting to a mountain view – we were working in a civilised part of this ancient continent. I use the word loosely. We were certainly in a town. I can’t remember what it was called but its charms were limited. No Benneton. No McDonalds. Perhaps it was rather civilised, after all.

Whilst the sun climbed I made sandy footprints down the KFC-less street. Parts looked medieval.

I was only mildly surprised at the odd vaporator sprouting on the skyline and a strange plastic creature tethered to a rail, hopelessly trying to look real. My suggestion that a pile of dewback droppings might add a gritty realism to the scene was ignored with a raised eyebrow. These artefacts were ours, of course. Theirs was the Cantina. Or rather, his…

It was at the far end of the dust road and like many of the buildings, igloo-domed. Sensibly, it was made of some kind of adobe glop as opposed to snow. Its proud owner stood outside. That was the bit we were going to use – the outside.

We smiled at each other. Daily gallons of desert-quenching Coca-Cola had performed their usual dental work on him, as on his friends. But the rotted-toothed smile was warm enough. The sun was well away by now.

We chatted in fragments of the languages we should have had in common. Like his friends, Ahmed was fascinated and impressed by our visit from the 20th century with its mighty techno-powers. He was so happy with his lot. Especially the goat / camel / Dinar / Deutschmark – or whatever they were swapping at the time – equivalent of £4 a day rent that he was being paid by the film company for the use of his home.

Knowing the huge amounts paid for English location shooting, I was shocked. He was happy with his lot but I didn’t think it was – a lot. I had once bought a book by one of the Marx brothers. I never did read it but I knew about the horrors of capitalism anyway. £4 was a scandal. A rip-off. A swindle.

It was unfair.

I told them.

They took me on one side, partly to explain that they were now waiting for me at the other end of the street. They also wished to point out the socio-economic effects of paying location fees beyond the market rate.

First inflation would eventually grip the entire country in its threatening fingers, hence jeopardising future film work as a national source of income.

Secondly, my new friend would be a rich man during our stay, dramatically improve his class status, grow superior, lose friends and eventually, after our departure, subside into socio-economic ruin and ultimate decay. So, far from being unfair, they were being very kind in paying him £4 a day.

Of course. I should have realised.

They were right.

At the other end of the street my high-tech transport awaited.

The famed land speeder was cooking in the sun.

LOOKS GOOD

Again I was travelling with Sir, Mark and Artoo strapped on the luggage rack. Next to him, perched, tourist class, on the back in assorted bits of cut-up gold – how thrilling twenty years later, at the Special Edition Royal premier, to notice my crutch flapping in the breeze – I waited to experience the first hover of my life.

To gently rise above the planet’s surface. To be free. To float on air – such stuff as dreams are made of.

The length of old carpet that I noticed, nailed to the rear bumper, looked decidedly earth-bound. I supposed this old rug had something to do with the battered look that styled everything in the movie, including me. But the long thin mirrors that fringed one side were radiantly clean. They duplicated the dust terrain around us.

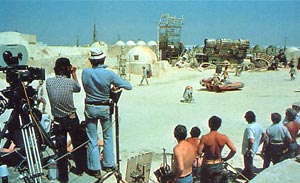

We prepared to hover. The camera watched us. The crew watched us. The inhabitants of this tiny hamlet watched us, believing that some sort of techno-miracle was about to happen before their sand-hardened eyes.

“Action!”

Mark swung the controls but I had no sense of being uplifted. Rather I had the sensation of being locked in a London traffic jam.

Funnelled by the carpet, the exhaust fumes streamed into my air conditioning unit, otherwise described as the small rectangular mouth in Threepio’s face. I blew them out again and nearly fell of the back of the speeder as Mark suddenly found second gear. I managed to grip onto the back of Obi-Wan’s seat bearing in mind his grand status as Jedi Master.

Mark, mistakenly I think, found the foot break and for a brief moment in time it appeared as though the Jedi Master and I were to be intimately united in first class. The land speeder, returning unhindered to second gear prevented this embarrassment.

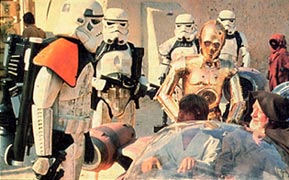

We turned a corner and after a brief chat with some pliable stormtroopers we swept down the street.

MOVE ALONG

There they were. The Camera. The crew. The crowds of local residents. My new friend. All marvelling at this peculiar progress.

I looked uncomfortable. Threepio does not approve of Mos Eisley. Also, I was uncomfortable. I was perched precariously and hovering was not the smooth experience I had imagined.

The exhaust fumes my still be getting up my nose: the old rug trailing in the dirt might be sweeping out the tire tracks; the tires might be hidden behind the mirror strips; but the suspension echoed every rut and bump on the planet’s surface. Still I tried, as did Sir A, to look regal. I thought we made a good impression.

GOING NOWHERE

Not for long.

The speeder slowed down, quite unrehearsed, in the centre of the street.

We weren’t even in smelling range of the cantina.

Mark wrestled the gently coughing vehicle to a hiccupping stop.

The clean desert air filled my lungs.

Our land speeder had run out of petrol.

OUT OF GAS

At sunset they watched us go as we steamed away in our cars and coaches.

Ahmed brushed away the diesel fumes.

He didn’t mind the breakdown.

He smiled, clutching his money.